The Lobster by Faye Griffiths

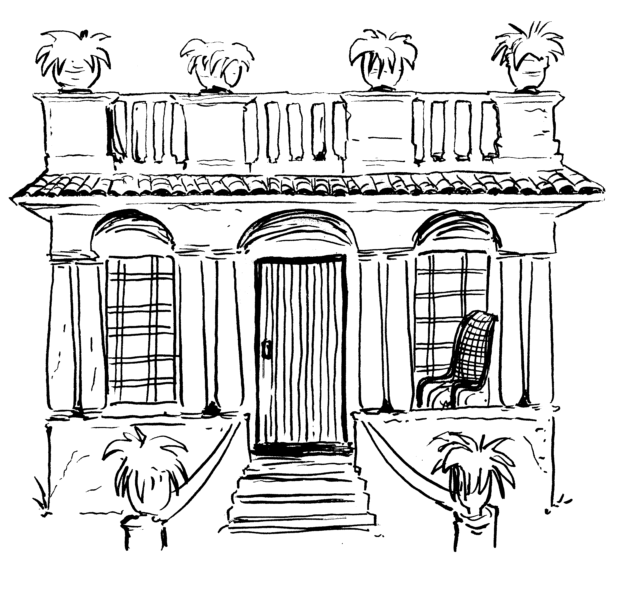

OUR HOUSE, A COLONIAL BUILDING with high ceilings and enormous hardwood doors, had been in my mother’s family since her great-grandparents’ generation, since long before the revolution. It was a fantastic house, with heavy shutters on each window that completely blacked it out at night, and an ornate tiled floor that was deliciously cool to hot and tired bare feet. At the front, looking onto the street, we had two rockers, which also belonged to some ancestor of my mother. Beside the rockers was a small table with a heavy ashtray for my father’s cigar that lived there permanently.

Although we hadn’t always taken boarders, the house had always been partitioned, as though it were purposely built for people to live semi-separately. I imagine, actually, that it had, and at one time our living area was that of servants to the colonial occupants. Our quarters were not uncomfortable, and we were not, of course, confined to them all of the time. During the day, the guests, who were all tourists, mostly left us alone to go to explore the sights or laze at the beach. Then, if there were no visitors in the house, I was permitted to sit in one of the rockers, or eat at the large dining table, whilst my mother cleaned the bedrooms and cleared their breakfast things away. But all of our essentials – my toys, our clothes, and the television,- were kept in what served as my parents’ bedroom, the room adjoining the small kitchen at the back. I slept on the sofa between the two rooms.

I can’t remember quite when we registered our house as a boarding place. I imagine that when my sister, who was a full decade older than me, married and moved out, my parents decided it would be more practical to do so with only one child in the house. Also, in the 90’s, things worsened economically, so that must have had some influence. My sister is actually my half-sister, which is why there is such a gap between us. My mother’s first husband left when she was three years old. He had the opportunity of leaving the country, which was more difficult in those days, and promised to send for his wife and daughter as soon as he could. My mother waited two years, and then, being the practical woman she was, forgot about him and considered her reality. She was still a young woman.

She had known my father nearly all her life, for he was a friend of her younger brother. Before the revolution, my mother’s family had been relatively, though not fantastically, wealthy. They had a little land and farmed and kept horses. I think a little of that superiority was passed down in the genes. My father, on the other hand, came from fishing people, although he himself was not a fisherman; he fixed boats, amongst other things. In different circumstances, I don’t believe they would have selected each other as partners, or, more accurately, my mother would not have accepted him. She was not beautiful exactly, but she had lovely hair, long and sleek, with very dark, serious, distant-looking eyes. She was quite tall for a woman and her body was naturally slender. In her thin face, her largish teeth looked slightly too big in her mouth, which, with the far gaze in her eyes, gave her an almost haunted look. As I have grown older, I have sometimes wondered whether that gaze was always in her eyes, or whether it set in after my sister’s father disappeared. I never once heard her mention him wistfully, nor caught her looking nostalgically at photographs (for anyway, there were only two), but it was there, that sense that she was sometimes elsewhere. When she accepted my father’s interest, I think it was out of a common-sense instinct not to remain alone, and to choose someone who would be truly kind to her then fatherless daughter. For my father was indeed a kind man, gregarious and jolly by nature and enormously generous of spirit. Physically, he could not have been more her opposite. He was about the same height, but looked smaller because he was very squat-limbed, with plump spatulate hands, and as he grew older, his face and middle grew fat. This suited his nature, and his fat cheeks made his small dark eyes appear more squinted, cheeky almost. An operation he had when I was only young to correct nodules on his throat had made his voice a little strained and high. Nonetheless, it did not stop him from speaking, not even a bit, for he loved to make conversation of any kind. Our house was rarely silent with his continual banter and my mother’s regular, almost mechanical interjections of assent in her lower, huskier voice.

I think it was this love of conversation that meant my father in no way objected to having guests coming and going almost continually. He was genuinely hospitable and enjoyed telling them the history of the town, the country, and our house – even though it was not really his. Equally, he enjoyed asking visitors about their home countries, where they were going on to, what they did for work, and what they did with their lives. Somehow, he even managed to converse with the guests who did not speak Spanish at all. My mother was also always welcoming and hospitable. In fact, many guests came to us after recommendations from their friends about her clean home and wonderful cooking. She cooked well – nothing fancy, just simple, well-flavoured, carefully made home food. However, her hospitality was more functional, asking what guests wanted for their meals and if they wanted to be woken in the morning. Although she enjoyed cooking, I don’t think she relished having people there. She enjoyed the occasional respite we were allowed during quiet periods. In these precious moments, she wore her long hair down, instead of in its usual simple twist into a clip.

The type of visitors we had varied greatly, and as we had two rooms to the front of the house, we often had five or six guests staying at once. Usually, they were all likeable and easy-going travellers, being on a budget and either unable to afford a hotel or preferring a more authentic experience. We had families, elderly couples whose children had grown, as well as younger childless couples and quite often pairs of female friends. One year, at Christmas, we were quite busy and my sister came with her baby to help my mother with the upkeep of the house. There was a German couple who were very pleasant and a single, nearly silent Japanese girl. The Germans spent Christmas Eve with us, at my parents’ invite, and for it we laid out the large table. Of course, we would not eat a special meal in the back bedroom. It was warm and jovial, and the couple loved my sister’s child, who was about a year old at the time. That evening, the Japanese girl left and my father went to the bus station (as he often did) to collect the next booked guests. It was quite late when the two young English women arrived, after a long bus journey. One of the girls, the quieter of the two, was sick with some stomach bug, so they simply filled in the required government forms and went to bed. In the morning, the Germans left and the girl cried when she said goodbye to us and gave me chocolate biscuits, which I shared with my father.

My mother cleaned the vacated room and then asked the girls if they wanted to move into the larger room and whether they wanted breakfast. They moved rooms, but didn’t take breakfast, as the more English-looking girl was still sick and unsure if she should eat. The darker girl, who had bright pretty eyes, said she didn’t feel hungry, and would just sit and read her book until her friend felt like going out. It was Christmas Day, so my father was not going to work and instead puttered around the house, doing odd repair jobs. The girl sat in her shorts and t-shirt with bare feet, rocking the chair steadily and reading her book. She was remarkably pretty, with quite an upturned little face and a youthful body. My father spoke to her a lot, and as her Spanish was reasonable, they were able to have some conversation. My mother was around, cleaning and putting away the good things that had been used for the Christmas meal. To listen to my father talk, he spoke no differently than he would to anybody else, but his eyes lingered just a little longer on the girl, who was friendly and ever so slightly coquettish. They didn’t have long chats, but it was almost as though he kept remembering something else he needed to mention to her. However, there really wasn’t that much information necessary for him to give; the town had, at most, three sites of interest, and the beach was the beach. But, perhaps out of boredom, or a wish to practise her Spanish, or a genuine warming to my jolly father, she indulged him, which stroked his ego. Even as young child, I noticed this, so I am sure my mother, although she would never have admitted it, did too.

Later that afternoon, the sick girl was much better and my mother seemed pleased that they agreed to eat that evening. But the girl said she would like something very simple that wouldn’t upset her stomach again. My mother nodded knowingly, but her friend remarked that she’d read in our visitor book that my mother’s lobster was unrivalled. My father quickly butted in that they had to try it. It was his absolute favourite meal, but at some point in recent years, the government had restricted the sale of lobster, so it could only be bought or sold for tourism. But, as we ran a guesthouse, my mother was often able to manipulate buying some extra that my father could enjoy as a treat. After a little convincing, both girls agreed they’d like to try the famous lobster.

They then went out for the late afternoon and my mother went to the market to buy their food. I was fed and she ate some too. Then the table was set and she began to prepare the meal for the girls, who were returning to eat at seven thirty. They arrived home early and my father asked how they had enjoyed the beach. The more English one had caught no sun, but the other had a healthy glow, which brought out her eye colour. As my mother finished cooking, they laughed with my father about the quiet girl’s lack of colour, and then the conversation turned to why the other had such a dark complexion for an English girl. My father joked badly that she was really an Arabian princess and she played along in a voice of pretend innocence, ‘Seor, por favor! No es verdad’. My father laughed luxuriantly at her response, and so it went on until my mother brought out the bread to accompany the meal. The girls sat and ate the bread and salad. Then the lobster, which glistened with juicy sweat, was brought out. There was always a pride in my mother’s face when the guests exclaimed how wonderful the food looked and smelled, for she knew they would not be disappointed. It was the first time the pretty girl had ever eaten lobster, and she made an obviously polite attempt to cut it with her knife and fork. She was not unsuccessful, but my father could not help showing her that the easier, and less mannered way, was to hold it in the hands and bite directly into the flesh. He demonstrated and the girls laughed. The girl imitated him and immediately exclaimed how delicious it was. She asked her friend if she would take a photo of her eating the lobster the right way, and as the girl set up the photo, she intimated that my father be in it too, as though they were both pretending to bite into it. My mother watched with a strange smile and a quiet look in her eyes. The picture did not take very well, so another was done in the same pose and the quiet girl showed it to my father, who approved heartily. The portion of lobster not served was left on a plate in the kitchen, and my mother placed some bread beside it and gave it to my father to finish. All was quiet; the guests were happy, my father had his favourite food, and my mother cleaned the dishes.

The following day, a Scandinavian girl arrived by herself. She was quiet and reserved, so she didn’t eat with the English girls. My mother was busy organising two sittings of breakfast and dinner. My father was back at work early that day. I think she would have liked for the two girls to pack themselves off to the beach, so she could have her peace, but the pale girl said she was still not completely well, so they took things slowly and lazed around in the room after breakfast. Before they finally did venture out, the chattier girl asked my mother about where she might be able to use the Internet in the town, and about some of the photographs that we had on display in the house. My mother gave her detailed information about where to find the Internet, but didn’t say very much about the photographs. She then asked if they wanted dinner again that evening at the same time, and what they would like. It was arranged that they would have chicken with sauce and it would be ready at seven thirty. There was a little difficulty as the girls tried to communicate that they didn’t want chicken on the bone, a combination of my mother not grasping what they meant and their lack of Spanish, but she finally understood and said it was no problem. She looked a little tired at the end of the exchange.

Their meal that evening was as good as any my mother ever cooked. but the girls said the chicken was very tender, perfect, and the sauce was delicious. They left a little on their plates, declaring regretfully that there was just too much and they could not finish it all, which was probably the truth. My father had been busy while they were eating, but afterwards, he went to speak to them and they asked him if he knew what time the buses left for the town they wanted to visit next. He joked that he knew, but would not tell them because he didn’t ever want them to leave. Both were chirpy that evening, the quieter one saying that she felt completely better. However, there was a flirtation only between my father and the pretty-eyed girl, who that evening was wearing a loose pink t-shirt that hung to reveal just the very top of her suntanned breasts. The girls were both very polite, picking up all their own plates and carrying them through into the kitchen themselves, but my father insisted that he take them, going to the friendly girl first to relieve her of them. He then offered them each a little of his rum, and took three glasses from the kitchen. My mother was clearing up and reminded him quietly that the German guest had to eat at the table soon. My father told the girls to sit in the rockers and relax, and he would pour the rum. The pretty-eyed girl told her friend that she probably shouldn’t have a drink until she was sure her stomach was better, but she said she was fine and was ready for one. She liked the rum, but her friend did not; it was strong and made her eyes water and splutter a little. My father laughed and rubbed her back and told her she just needed to have some more and she would be better. As the German girl came to eat, my father helped my mother serve up her food and the English girls politely made an exit to their room, retiring early for bed.

In the morning, they took breakfast and then went to try to collect tickets for the night bus. They were successful, so all they had to do that day was to not go too far, as they had to be at the station at six. The bright-eyed girl spoke more Spanish, so she arranged with my mother for them to stay at another boarding house in the next city. It was booked up due to the time of year, so my mother spent a good half hour finding them another house where they could stay. The girls were thankful, but not fully aware how much effort my mother had gone to on their behalf. When the time came for them to leave and take their bus, my father was just returning home. It wasn’t quite dark, but he insisted upon escorting them to the bus station, even though it was less than a ten-minute walk and they knew the way. The girls were very firm about not putting anybody out, and almost forcefully had to reject his offer. They thanked both my parents greatly for their wonderful hospitality, and at their request, wrote a nice note in our visitors’ book, and then they really had to get going. It was bordering on embarrassing the way my father was making more than his usual show of sadness at guests leaving, and eventually, the quieter girl seemed almost irritated by it and simply moved away. My father lingered at our large doors a bit longer, breathing in the diesel air in the warm, heavy evening. Then he came inside and puffed a little on his cigar in the rocker, before taking a wash – something he usually did straight away.

The following day, the quiet German girl left after breakfast, and my mother cleaned both rooms in preparation for three guests from France who were arriving that evening. We were told it was two men and a woman, and that they needed both rooms. My mother had a long day, having problems exchanging some money to buy soap for the new guests. She was also anxious because she didn’t know how late they would arrive and wasn’t sure whether to buy fresh meat in case they wanted to eat. She wasn’t often fractious, but on the occasional times like these, I knew to keep away and allow her to bang cupboard doors a little harder than necessary, and walk home from the shops at the pace she set. When my father came home from work, she was still in the same mood, but quieter and more focused on her work. He asked her what the setup was with the French three and she answered with a shrug that it was probably just three friends, two single men and a single woman. My father made a joke about how you never knew with the French, but I didn’t see my mother acknowledge it in any way.

They arrived at nearly ten o’clock, as their bus had been delayed. I was allowed to stay up until they arrived, but then had to go immediately to bed with the big lights on, which wasn’t a problem, as I was quite used to that. The house smelled polished and felt safe and homely with the shutters blocking out the night. There was the faintest breeze, which made the night feel much lighter compared to the day that had gone before. I heard my mother speaking to them and completing the paperwork, and my father also saying hello and welcome. All three were photographers of some sort and were on a sort of working holiday. However, they were actually a couple and a single guy, and he was the woman’s younger brother. The woman went to bed straight away, but I heard my mother convince the men to let her prepare them some cheese and bread and they each opened a beer that they’d brought with them. Then she retired, for they requested an early breakfast. I heard her telling my father that she needed to also get up early when he did, but they made no other conversation that night.

The French guests got up early, but took a long time over breakfast. They talked a lot amongst themselves and asked for an extra flask of coffee, which they praised for its excellent flavour. My mother seemed to be moving with more ease, more delicately than the day before, and there was more presence in her eyes. I wanted them to finish and go out so that I could eat my breakfast at the table, but they asked my mother lots of questions whilst still seated. They wanted to know about the historic sites, but also about nearby rural areas, or areas where locals congregated, unusual things like that. Only the woman spoke Spanish, but the two men directed their questions in French to my mother nonetheless. They asked for their evening meal to be prepared quite late that evening and my mother said that was fine. When she asked what they would like to eat, they were quickly emphatic that they just wanted very traditional local food. My mother said that it would be impossible for her to prepare anything else, and when the French woman translated, they all laughed lightly. I didn’t understand why they all did, but I found it unusual that anyone should laugh at my mother.

They returned even later than expected that evening, so my mother was anxious about keeping the food warm, but not overcooking the meat. She, my father and I ate a very simple meal that evening, and she ate standing up in the kitchen, keeping guard. It was worth her efforts, for the French were rapturous in their praise of their dinner. They had bought a few bottles of wine, which was fairly luxurious for us, and they insisted upon my mother and father taking a glass each. They deliberated over the meal and frequently topped up the wine and exclaimed about how the chicken was cooked to perfection and the vegetables were exquisite. Every time my mother tried to clear the table, they asked her about where she had learned to cook and said that she ought to open a restaurant. My father enjoyed their company too, but he made a reasonably accurate, mocking impersonation of their accent whilst smoking his cigar in the back – because they were still luxuriating around the table until late. My mother hushed him with her dark eyes and moved with just the faintest momentum that implied irritation.

At breakfast the next morning, they were quieter, but they said something strange about wanting to photograph my mother cooking, just her hands more or less, and asked her whether she would mind. She just laughed it off lightly. It was the evening of the 30th, and my father’s 39th birthday. He never made much of a fuss, just a few glasses of rum more than normal, and usually saved himself for the celebrations of the 31st anyway. Nonetheless, my mother mentioned that we would be having a family meal for my father’s birthday, and that the party was quite welcome to join us all. They accepted the invitation warmly and assured her they would return to eat much more promptly that evening and apologised for their rudeness the day before in that regard. Then my mother did a strange thing. She asked them if they would like to have chicken again, but she could make a Creole-style sauce this time. The French immediately exclaimed that that would be superb and that they could hardly wait. They left for the day and my mother set out immediately for the meat market. I had the task of peeling some vegetables and making a trip to my sister’s house to inform her of the arrangements.

When I arrived home that afternoon, the house smelled fresh and aired. There was a small handful of flowers in a vase on top of the large table that she had already managed to get out by herself. My mother had everything that was to be cooked ready and laid out in various strategic places around the kitchen. When she re-appeared from the smaller bedroom, her hair was different. Instead of being in its usual twist in a clip, it fell loosely over her bony but strong shoulders. It made her eyes seem more widely spaced than usual. She issued me with a few small errands, such as polishing the cutlery, and began her preparations in the kitchen. I asked her questions about the guests, but the words seemed not to register. Her eyes seemed absent, but not in the usual way.

The French party arrived home early, before my father, and whilst the woman went to freshen herself, the men produced more bottles of wine, and the one who was not the husband asked about photographing my mother’s preparations. She lowered her eyes under the curtains that her hair formed around them and gave a gentle shrug of assent. My sister gave me an inquisitive and mocking glance as the young man snapped away at strange angles as my mother’s angular and hard hands boned the chicken. It was then that my sister exclaimed with alarm that there was no lobster. My mother stopped suddenly and the French photographer seemed also to stop instinctively. My mother gave a little half-laugh and shrugged her explanation; the queues at the fish market looked terrible, and they could get some for tomorrow. It wasn’t a big deal, she told my sister. Ory, at the age of thirty-nine, wasn’t going to cry because they didn’t have lobster on his birthday. It was tradition, though, as far as I could think back, for my father to have a prime succulent lobster as his birthday meal. My mother always cooked it in her garlic sauce and he would always declare that it tasted better every time. She hastened to add that the French people had all asked for the chicken, but when my sister said it wasn’t too late to still run down and buy one, my mother rubbished that suggestion, saying that any catch bought then would be dry and not fresh after lying there all day. Then she asked my sister to slice some bread and carried through some plates for me to lay out.

When my father entered the house an hour later, maybe less, the scent of chicken filled the whole place, which was unusual, as the high ceilings usually prevented that from happening. He must have noted the scent of the chicken, but presumed that it was just for the guests and my mother. The French, who were already supping wine and had nibbled on the sliced bread, greeted him warmly. His jovial face thanked them and he said he would quickly wash – as it was his birthday – whilst my mother served up.

He rubbed his fat little hands together quickly and planted a brusque kiss on my mothers’ cheek, which was hidden behind her hair, which he had made no remark about. When he re-emerged, the food had just then been dished onto everyone’s plate, and the French man was generously filling my father’s glass with red wine. As the French woman made a toast to the health of her hosts and their fantastic hospitality, my father’s eyes scanned the table and registered the chicken on his own plate. His smile faltered for just a second and his puzzled eyes searched my mother’s. Her eyes were down in humble receipt of the final line of the toast: to Ligia, the most wonderful cook.

*********

Enjoy this culinary masterpiece along with the rest of SN9: Fat Tuesday – available on Amazon now!